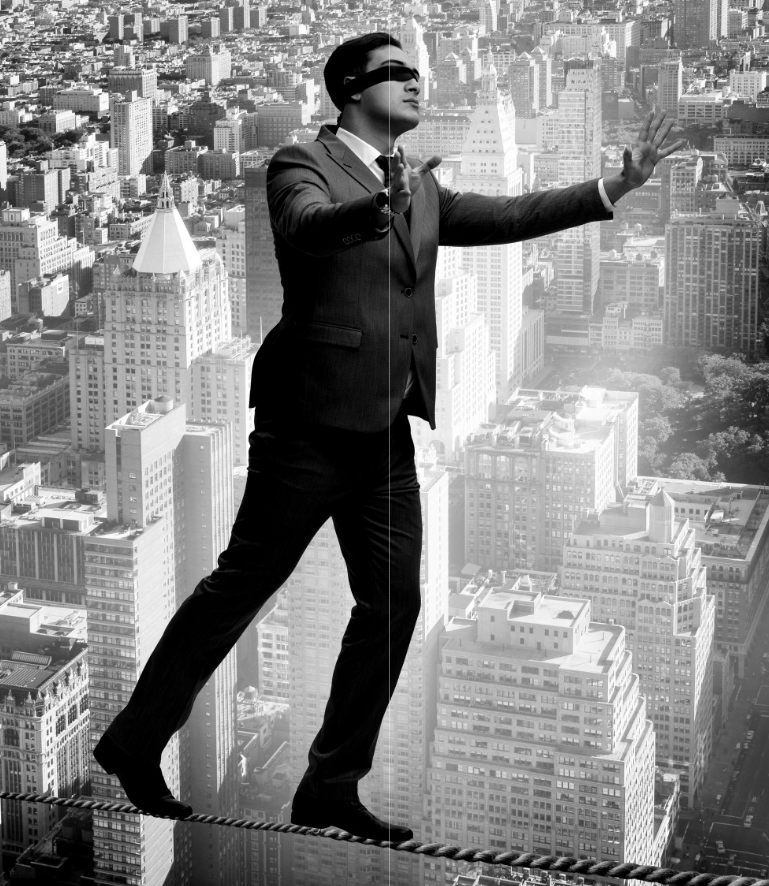

Mark McLaughlin points out that there may be unfortunate consequences for clients who turn a blind eye to their agent’s errors

Tax return errors by taxpayers are not uncommon. This is perhaps understandable, given the complexity of the UK tax system and the potential for misunderstanding tax law. It is undoubtedly an important reason why many taxpayers engage agents to deal with the preparation and filing of their tax returns.

Who’s to blame?

However, what if an error is made in the taxpayer’s return by an agent? These days we live in a blame culture, and taxpayers might feel justified in blaming their agents as a convenient escape from a penalty for a tax return error.

Understandably, agents will normally seek to detach themselves from blame for tax return errors. If the agent admits responsibility, they leave themselves open to a possible professional negligence claim. Furthermore, an acrimonious dispute could result in a complaint being made to the agent’s professional body (if they are regulated by one).

Reasonable care?

The penalty legislation concerning agents broadly provides that a taxpayer is liable to a penalty if the return contains a careless error and is given to HMRC on the taxpayer’s behalf. A loss of tax is brought about carelessly if the taxpayer fails to take reasonable care to avoid bringing it about (TMA 1970, s 118(5)).

Unfortunately, there is no statutory definition of ‘reasonable care’. The question of whether reliance on an agent constitutes reasonable care will depend on the particular facts and circumstances of the case. This can be a tricky issue, which has resulted in disputes and litigation. For example:

In AB Ltd v Revenue and Customs [2007] STC (SCD) 99, it was held that a taxpayer who takes proper and appropriate professional advice with a view to ensuring that his tax return is correct and acts in accordance with that advice (if it is not obviously wrong) would not have engaged in negligent conduct.

Subsequently, in Hanson v Revenue and Customs [2012] UKFTT 314 (TC), the taxpayer disposed of loan notes during 2008/09, resulting in chargeable gains for capital gains tax (CGT) purposes. His accountants erroneously claimed a form of holdover relief on the taxpayer’s behalf to mitigate the CGT charge on the disposal. The First-tier Tribunal (FTT) held that the taxpayer had taken reasonable care to avoid the tax return error. He had instructed an ostensibly reputable firm of accountants, who had acted for him for many years.

The advice given was seemingly within their expertise, and there was no reason to doubt their competence or their advice that the relief was available. In these circumstances, the taxpayer was entitled to rely on the accountants’ advice without himself consulting the legislation or any HMRC guidance.

In Gedir v Revenue and Customs [2016] UKFTT 188 (TC), the FTT held that the taxpayer took reasonable care despite a tax return error. In reaching that conclusion, the tribunal noted certain ‘essential elements’. In particular, the taxpayer consulted an adviser he reasonably believed to be competent; he provided the adviser with the relevant information and documents; he checked the adviser’s work to the extent that he was able to do so; and he implemented the advice.

Obviously wrong

However, there are limits to the circumstances in which taxpayers can argue that reasonable care has been taken, such as where an agent’s error is clear and obvious. In Collis v HMRC [2011] UKFTT 588 (TC), the FTT judge stated: “That penalty applies if the inaccuracy in the relevant document is due to a failure on the part of the taxpayer (or other person giving the document) to take reasonable care. We consider that the standard by which this falls to be judged is that of a prudent and reasonable taxpayer in the position of the taxpayer in question.” Unfortunately, that standard has proved too high for taxpayers in some cases.

For example, in Shakoor v Revenue and Customs [2012] UKFTT 532 (TC), the taxpayer disposed of two flats in July 2003. His accountant’s advice had been that the disposal of the flats would not result in a CGT liability (on the basis that private residence relief applied due to an extra-statutory concession), even though the taxpayer had not resided in either flat at any time during his period of ownership. The taxpayer noticed that his tax return for 2003/04 contained no reference to his disposal of the flats. He questioned this with his accountant, who told him that as the disposal was exempt, there was no requirement to disclose it in the tax return. Unfortunately, the FTT held that the accountant’s advice was obviously wrong, and that the taxpayer ought to have realised that it was obviously wrong or so potentially wrong that it called for further explanation or justification.

Turning a blind eye

In Bakery Badjie v Revenue and Customs [2023] UKFTT 537 (TC), HMRC issued tax return enquiry closure notices and penalties to the taxpayer for 2016/17 to 2019/20. The penalties were calculated based on careless behaviour, as records had not been kept supporting large expense claims. The taxpayer appealed against the penalties. He argued that he relied upon his accountant and had no knowledge of the expenses claimed on his behalf. He did not review his tax returns and had no knowledge of the claims until HMRC told him. He had not provided details of any expenses to the accountant, who claimed them on the returns. The taxpayer contended that he was not careless.

HMRC pointed out that during a telephone call the taxpayer informed HMRC that his brother had introduced him to an accountant who could get him a refund, and that he did not have receipts to support any of his expenses. HMRC considered that this demonstrated a lack of reasonable care.

The FTT noted that the taxpayer was within the PAYE regime, and that the expenses claimed for 2016/17 to 2019/20 equated to 49.63%, 53.43%, 57.74% and 51.86% of his income for each tax year.

The taxpayer clearly knew that his expenses claims would result in a tax refund, even though he did not have any receipts to support his expenses claim, as he had chased up HMRC for repayments. In addition, the taxpayer admitted to HMRC that he had “told the accountant what he spent and left it to the accountant to complete the tax returns”. The FTT considered that the taxpayer was not ignorant of what was going on. He gave information to his accountant without any supporting documentation, and so it upheld the penalties.

One error, two penalties!

If an agent accepts responsibility for a tax return error, the taxpayer may be forgiven for assuming that they have successfully escaped a penalty. However, this is not necessarily the case.

It is possible for both the taxpayer and the agent to be separately liable to a penalty in respect of the same error (FA 2007, Sch 24, para 1A(3)), if the taxpayer has not taken reasonable care to avoid the error. The taxpayer would be liable under the general penalty rule that applies to taxpayers, and the agent would be liable to the ‘other person’ penalty.

However, there is a limit to the overall liability to penalties. The aggregate penalties will not normally exceed 100% of the potential lost revenue (although a higher maximum than 100% can apply if the error involves an ‘offshore matter’ or an ‘offshore transfer’) (FA 2007, Sch 24, para 12(4), (5)).

HMRC’s benchmark

HMRC’s view (in its Compliance Handbook Manual at CH84540) is that: ‘[a] person cannot simply appoint an agent and deny responsibility for their tax affairs… The person has to show that they took reasonable care, within their ability and competence, to avoid default by their agent.’

The benchmark set by HMRC is of a taxpayer who goes to an apparently competent professional adviser; gives the adviser a full and accurate set of facts; checks the adviser’s work or advice to the best of their ability and competence; and adopts it. In those circumstances, HMRC accepts that the taxpayer will then have taken reasonable care to avoid inaccuracy on the part of themselves and their agent.

Conclusion

Of course, HMRC’s counsel of perfection is not legally binding, and in practice the taxpayer’s actions will often fall below such high standards. As mentioned, in practice each case will need to be considered on its own merits.

- Mark McLaughlin CTA (Fellow) ATT (Fellow) TEP is Editor and a co-author of HMRC Investigations Handbook (Bloomsbury Professional)