Mike Lewis explains some of the reasons for the record low level of trust in the UK’s tax authority.

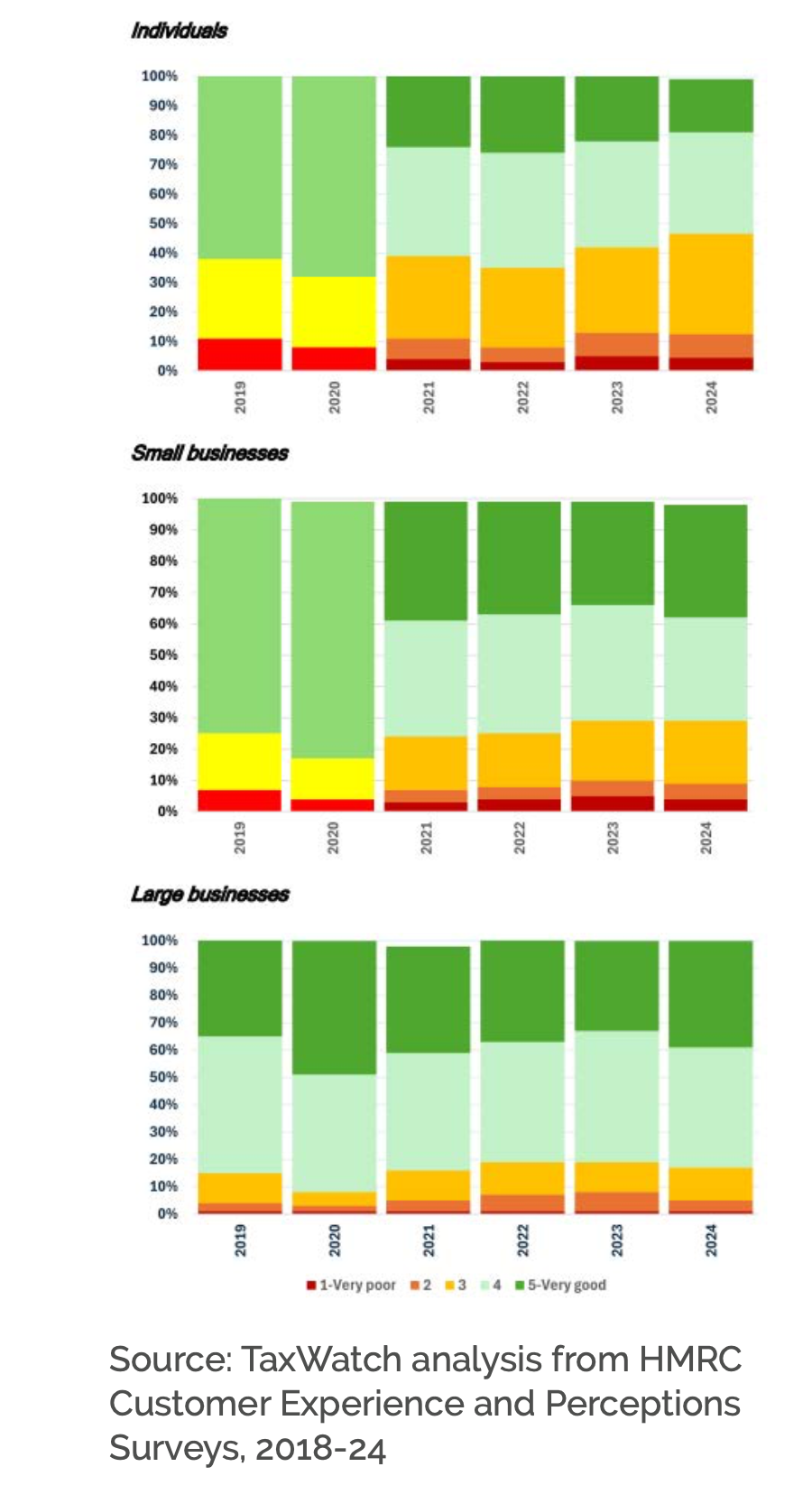

HMRC is never going to win a Whitehall popularity contest. But tax morale depends upon taxpayers at least feeling like they are being treated fairly by the tax authority. HMRC’s own attitudinal surveys suggest that taxpayer trust, particularly amongst individuals and small businesses, is at historically low levels. For reasons we discuss below, figuring out why is one of the most important and overlooked questions in UK tax policy.

Whether justified or not, just 30% of individuals surveyed last year who had dealt with HMRC agreed that “HMRC would admit if they made a mistake”. And only 27% of surveyed individuals agreed that HMRC “applies penalties and sanctions fairly to all taxpayers”, also a historic low.

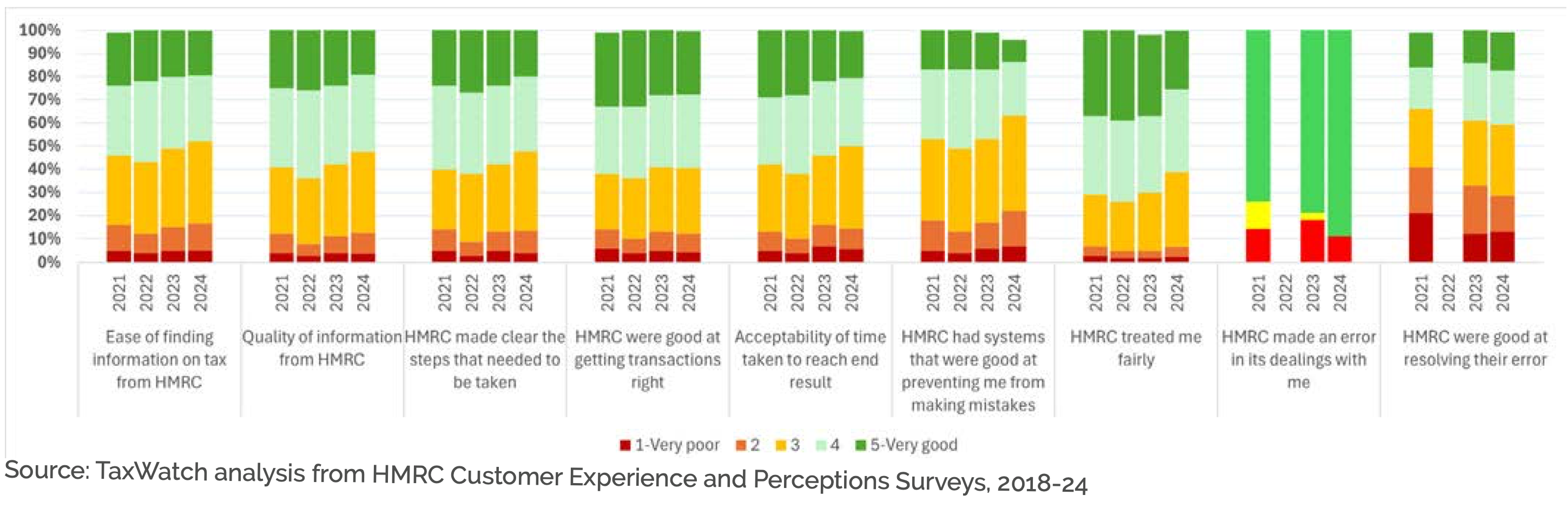

TaxWatch tracks these metrics over time. Our latest annual deep-dive into the nation’s tax administration, State of Tax Administration 2025, finds that across almost all trust and confidence metrics, scores have declined since the pandemic amongst both individuals and small businesses. Nearly one in 10 individuals and small businesses surveyed by HMRC last year reported that the tax authority had made an error in their dealings with them. And just 52% of individuals who dealt with HMRC reported a good experience last year: an eight- year low.

Of course, declining trust and confidence in institutions is much bigger than HMRC. From the Post Office’s wrongful prosecution scandal, to the thousands of unpaid carers hounded by the Department of Work and Pensions for erroneous benefit overpayments, there is a prevalent feeling amongst the public that public-sector bodies enforce rules in ways that are rigged, or incompetent, or both.

The recent news that HMRC appears to have frozen the child benefits of thousands of parents, based on flawed Home Office travel data that incorrectly labelled many of them as having left the country, seems to fit this pattern.

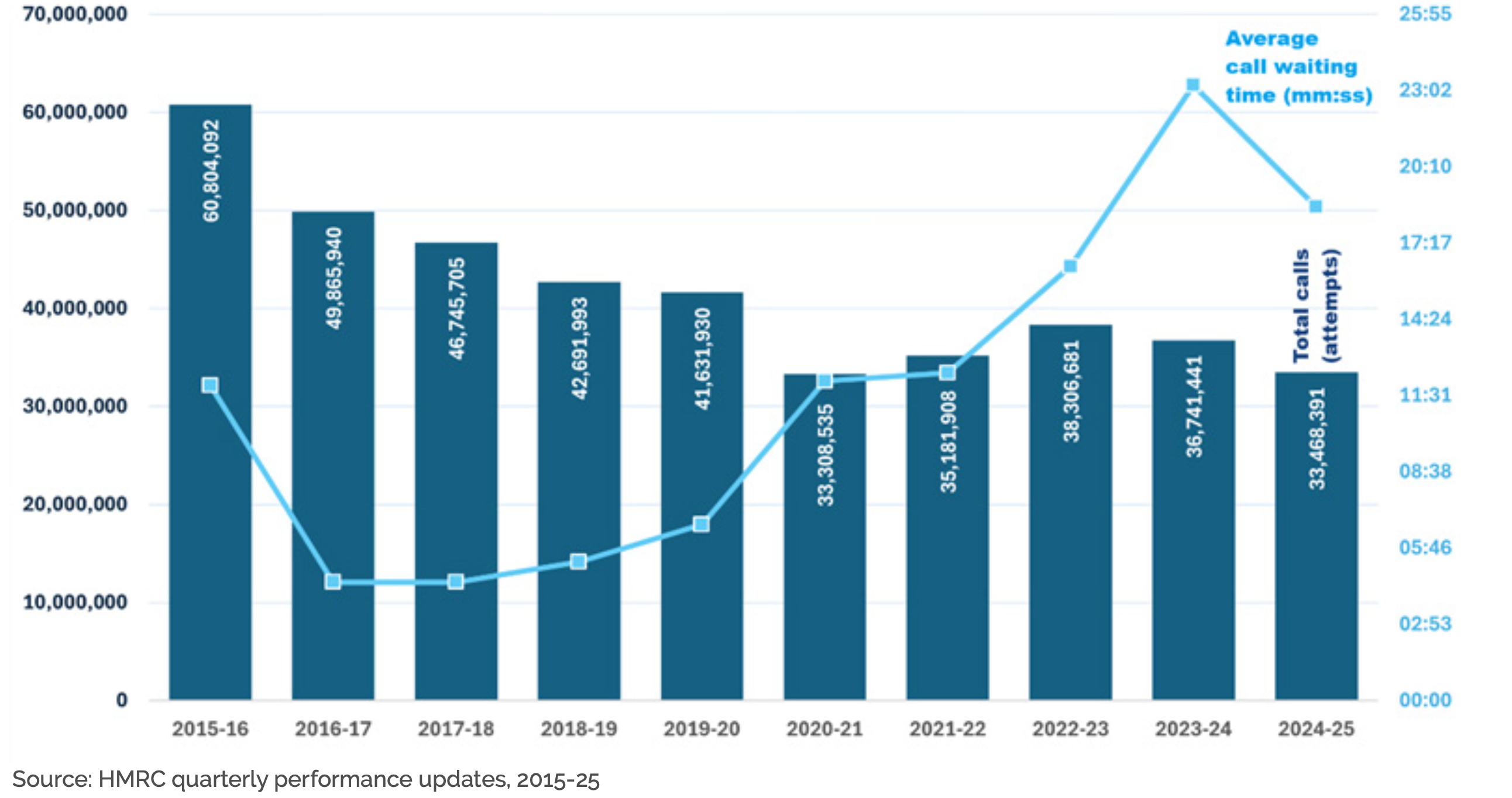

But HMRC’s taxpayer trust and confidence metrics also reveal a striking disparity. The only category of taxpayer that is overwhelmingly and persistently happy with how HMRC treats them are the elite group of the 2,000 biggest corporate taxpayers serviced by HMRC’s Large Business Directorate. This is perhaps unsurprising: since they pay a very large proportion of Britain’s corporate tax take, these platinum-card taxpayers each have an individual compliance manager. We can assume their tax departments were not amongst the taxpayers and agents who spent over 1,186 years collectively waiting on the phone to HMRC last year. Some 83% of large businesses reported a ‘good’ or ‘very good’ experience with HMRC last year, and 87% agreed that “HMRC treated my business fairly”, compared with only 61% of individual taxpayers.

Proof is in the pudding

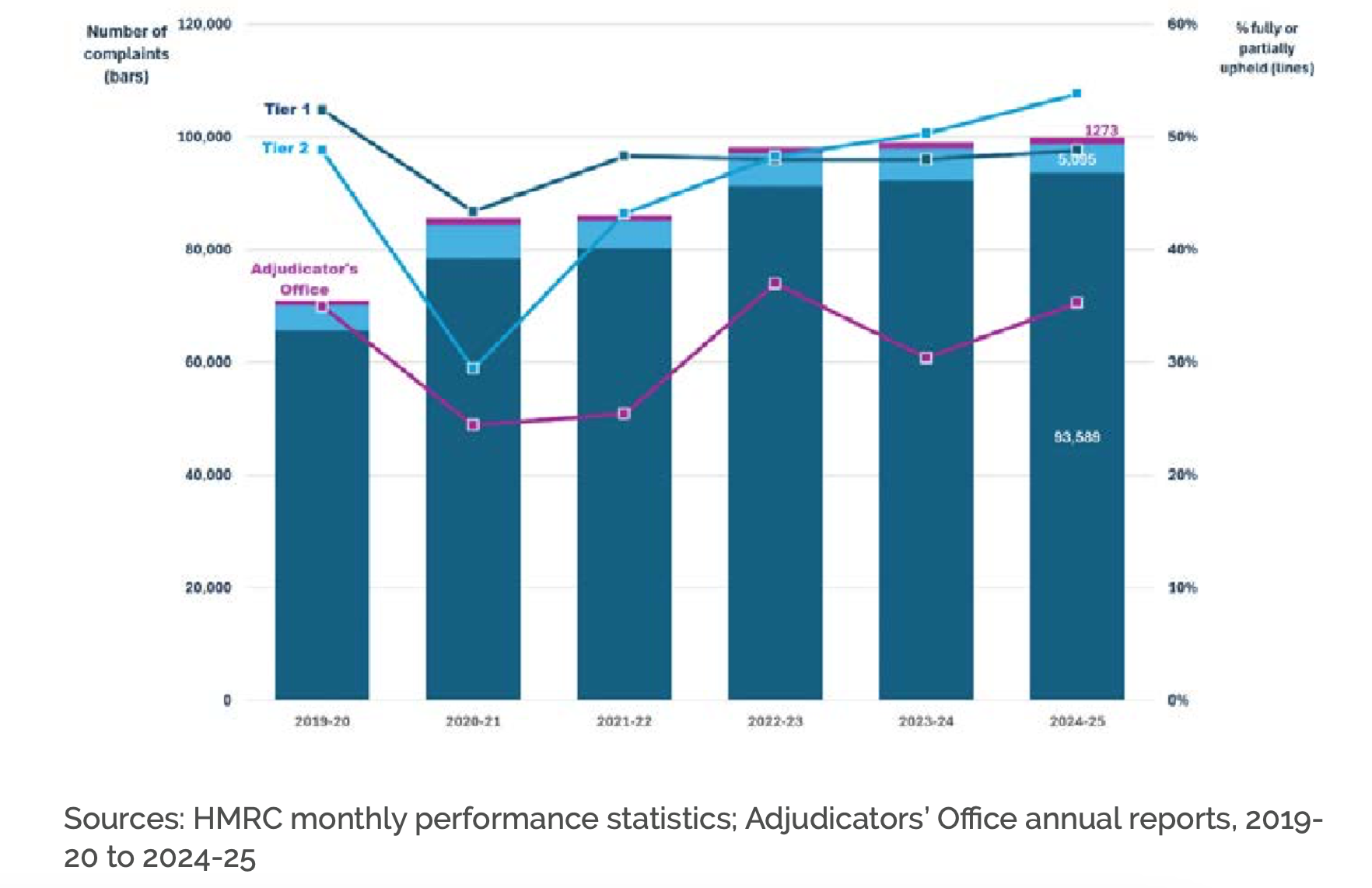

It’s easy to dismiss individual and small business dissatisfaction simply as the chagrin of the emptied purse. But their perceptions of worsening treatment are to some extent backed up by the outcomes of complaints and appeals. Around half of all taxpayers’ complaints to HMRC about their treatment were fully or partially upheld last year, a 42% increase from pre- pandemic levels.

HMRC is undeniably getting better at counteracting non- compliance. Compliance yield reached £48 billion in 2024-25, up 15% from the previous year.

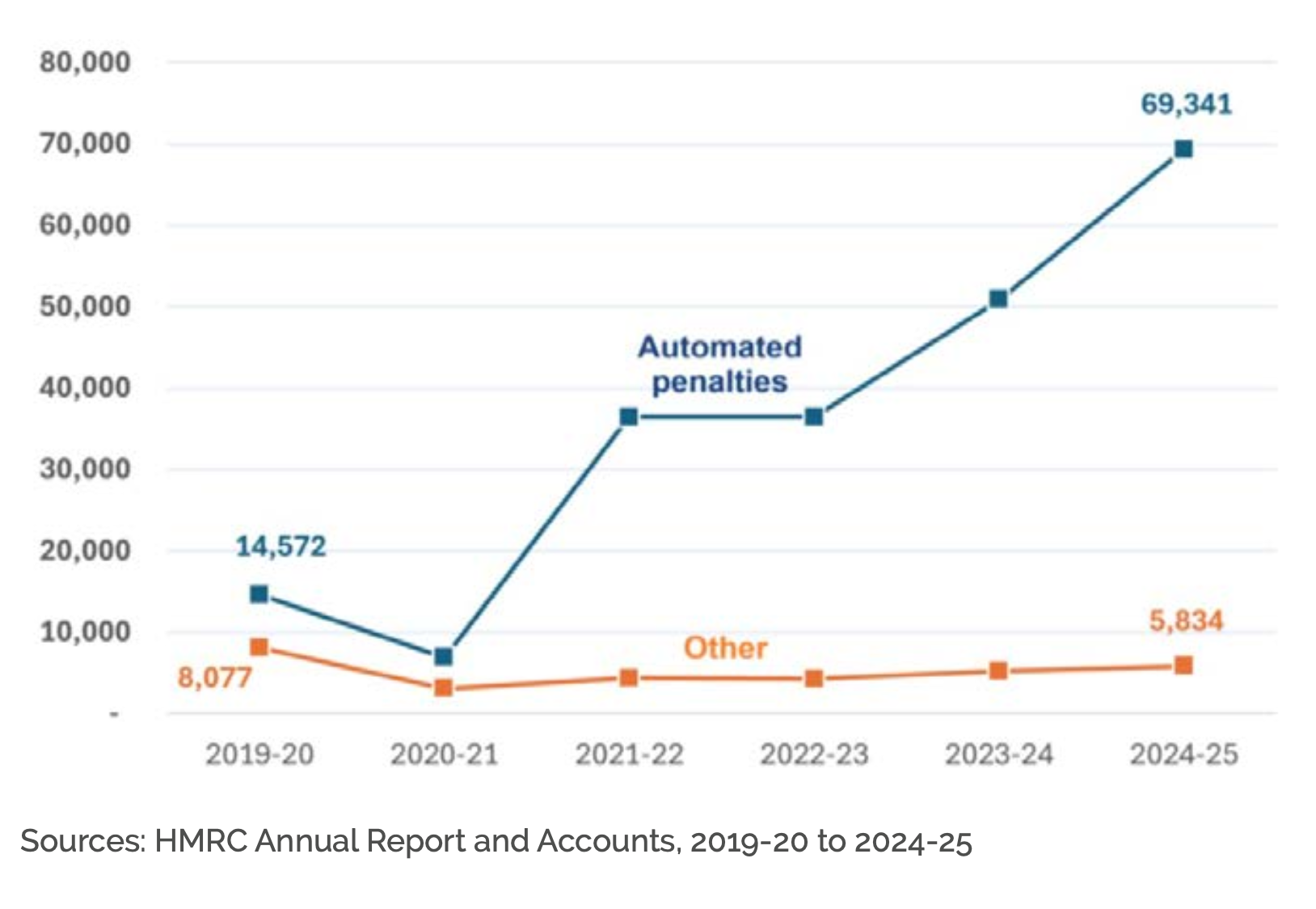

Annual ‘Cash Expected’ from compliance activities has nearly doubled in value since 2020-21 rom £7.4 billion to £14.2 billion, reflecting some very large recent compliance cases. However, amidst rising compliance yield, some areas of everyday and automated tax enforcement are either alarmingly error-prone, or are hitting some of the most vulnerable taxpayers hardest. For instance, where taxpayers requested statutory reviews for automated penalties – such as for late payment or late submission of a tax return – an astonishing two-thirds of such internal reviews found that HMRC had incorrectly applied the penalty, compared to just 12% of other types of assessments and penalties reviewed. There were 70,000 appeals of automated penalties last year, a five-fold increase since 2019.

The high success rate of challenges to automated penalties is testament to the independence of the reviewers within HMRC’s Legal Group. But it also shows that HMRC continues to have a serious and persistent problem in incorrectly applying automatic penalties since the system was introduced in 2011. Some 100,000 late-filing penalties are given every year to low-income individuals who owe no tax at all. In the worst cases, where mental health or other problems disrupt individuals’ repayments, these can spiral to five-figure sums.

A new penalty regime under Making Tax Digital for Income Tax Self Assessment from April 2026 will abolish the first late-filing fine for self-assessment taxpayers (though it will also increase the second one to £200). However, there is no date yet to apply MTD and its revised penalty regime to taxpayers with incomes under £30,000.

Meanwhile, rapidly accruing penalty regimes continue to exist for other taxes and taxpayer groups.

A worried Treasury?

Beyond individual distress, declining taxpayer trust and persistently high errors matter – for two reasons. First, if ordinary people don’t feel that HMRC treats them fairly compared with other taxpayer categories, then they are less inclined to declare all their income properly and pay their taxes. November’s Budget promised a new 350-strong team of criminal investigators to crack down on small business tax fraud, especially on the High Street. But the problem is clearly growing.

Over a third of small businesses’ tax returns mis-state their income by more than £1000. Meanwhile, out-of-court settlements between HMRC and non- compliant multinationals – however justified by enforcement efficiency such settlements may be – can feed the impression that there’s one rule for small taxpayers and another for big ones.

There’s a similar story about HMRC’s pursuit of disguised remuneration tax scheme users.

We can’t and shouldn’t adjudicate on how HMRC has handled this incredibly fraught area. But it is certainly true that those who profited from organizing such schemes, or more outright evasion, are very rarely prosecuted. Though HMRC has the statutory power to name and shame promoters of defeated tax avoidance schemes, TaxWatch knows of no instance where a recipient of such an ‘enabler’ penalty has been publicly named in this way.

Likewise, in 2017 the UK introduced a new corporate criminal offence of failure to prevent facilitation of tax evasion – intended in the wake of the HSBC Switzerland scandal to make banks and other firms pay if they helped others evade tax. It has taken until August 2025 for HMRC to bring the first prosecution under this law – against a small accountancy firm in the northwest of England. The case won’t even come to trial before mid-2027.

Second, this government’s tax and spending plans are unusually reliant on boosting HMRC’s ability to both inspire and enforce tax compliance. The untold story of the last Budget was that the Chancellor is betting the house on boosting HMRC’s ability to tackle tax non-compliance better.

Measures to close the ‘tax gap’ were in fact collectively the Budget’s third-largest revenue- raising measure, after income tax threshold freezes and pension NIC changes, though they were near-invisible in the public and media debate. They are forecast to bring in an additional £2.6 billion by 2030-31. Together with measures announced in Autumn 2024 and Spring 2025, the government is now expecting to raise £8.8 billion annually from improved tax compliance by 2029-30.

Yet only 26 of the 6,700 new compliance and debt management staff that the Chancellor has promised are yet in post (a further 718 new compliance staff are still in 18-month initial training). IT and comms systems are creaking.

Though HMRC’s ability to respond to taxpayer communications is improving, it still missed departmental targets in 2024-25, after a £51 million funding boost in 2024 for answering calls and correspondence. The average call waiting time fell for the first time since 2016-17 but is still four times longer than in the mid- 2010s, when HMRC was receiving nearly 50% more calls.

In 2024-25, some 6.5 million calls – nearly 20% of the total – were not answered at all.

If tax compliance doesn’t increase in the way that the government expects, the Chancellor’s promised spending plans, from SEND to expanded child benefits, are simply undeliverable.

Resourcing HMRC compliance and customer services functions has a powerful return on investment. But HMRC needs to recruit and retain experienced staff – its annual staff turnover is over 8%, above the Civil Service average. It needs to fix comms and IT systems, particularly as Make Tax Digital (MTD) progresses for Self-Assessment: less than six months out, TaxWatch research indicates that up to 20% of MTD software interfaces (APIs) are not yet “stateful” – they can’t retain data – and so can’t yet be fully tested.

Finally, and critically, HMRC needs to help make individual and small business taxpayers believe that they are being treated equitably. That isn’t just a question of fairness – it may have an outsize impact on the nation’s finances, too.

TaxWatch’s annual ‘State of Tax Administration 2025’ report was published on 17 November 2025.

It is available here.

- Mike Lewis, Director, TaxWatch